March 8th: International Women’s DayOMCA CollectionsSee Red...

See Red Women’s Workshop

Peter probably was infected within a few years, maybe even a few...

Peter probably was infected within a few years, maybe even a few months, of his arrival in San Francisco. By the time he tested positive in 1985, he said, “the party was over.” In those days, a decade before drugs were developed that could arrest the disease, anyone who tested positive expected to die quickly, gruesomely. Doctors did little to discourage that thinking. Make the most of the little time you have left, patients were told.

“From that day on,” Peter said, “you’re always living with that in your head.”

Just a year earlier, Peter had started a travel agency in the Castro with a friend, Jonathan Klein. For a few years, theirs was a joyful, flourishing business catering to the gay community. As the AIDS epidemic grew, they began charting final trips for young clients who needed oxygen or wheelchairs to travel.

His doctor died of AIDS just months after Peter tested positive. Friends from high school and college died. In the Castro, where he lived and worked, men his age stooped over canes, withering away. Peter offered the spare bedroom in his apartment as a refuge for families and friends keeping vigil over loved ones.

“I saw one of the great world epidemics unfold in front of my eyes,” Peter said. “I have to carry that with me the rest of my life.”

Kevin tested positive for HIV. At 27, he felt he’d been handed a death sentence. Now 56, Kevin doesn’t have a job and rarely writes. He spends hours by himself in his apartment overlooking the Castro. Sometimes he’s there all day.

If he’d thought there was any chance he would outlive AIDS, he might have stayed in school. He might have saved for retirement or bought a home. Instead, he said, “I was preparing all that time to die.”

Today marks the 89th birthday of Cesar Chávez, who was born on...

Today marks the 89th birthday of Cesar Chávez, who was born on March 31, 1927, in Arizona.

History will judge societies and governments—and their institutions—not by how big they are or how well they serve the rich and powerful but by how effectively they respond to the needs of the poor and helpless.

In our boycotts, we always assumed that supermarkets and other corporations must take seriously the needs of society, and especially the needs of the poor, even though they are answerable only to their stockholders for the profits that they earn. We often asked, if individuals and organizations did not respond to poor people who are trying to bring about change by nonviolent means, then what kind of democratic society would we become? And some corporations did respond by joining with millions of Americans in honoring the farm workers’ boycotts.

If corporations and other social institutions can recognize their moral responsibility, how much more should we expect from a great university that is supported by all the taxpayers, including the farm workers, particularly when that university is a direct cause of hardship and misery for the poorest of the poor in our society? It is appropriate for the people to expect that an institution responsible for educating their children will be an example to the young by demonstrating through its policies and deeds its commitment to a just and peaceful world. How can the university teach justice and respect for the freedom and dignity of all people when it practices the opposite with its money and its people by refusing to live up to its own moral and social obligations?

“The Farm Workers’ Next Battle,” March 25, 1972

Pictured: Chávez in July 1972. Wikimedia Commons/U.S. National Archives and Records Administration

April 6, 1994: Rwandan President Juvénal Habyarimana is killed;...

April 6, 1994: Rwandan President Juvénal Habyarimana is killed; the Rwandan genocide begins.

On the evening of April 6, 1994, an airplane carrying Rwandan president Juvénal Habyarimana was shot down over the capital of Kigali, killing all on board. Habyarimana’s sudden death set off a campaign of violence, organized by a circle of political elites - a violence that first targeted Hutu moderates, and that devolved into frenzied bloodshed enacted along ethnic lines; it was a violence that stretched beyond its initial outburst into May, June, and July and came to be understood as genocide. Within one hundred days, the Hutu-led government and state-supported militias and paramilitary forces (often not even organized units but simply civilians armed with machetes and makeshift weapons) slaughtered some 800,000 Rwandans, mostly Tutsi people, and in total some 15-20% of the total Rwandan population.

At the time of Habyarimana’s death, the Arusha Peace Agreement between the Rwandan government and Tutsi-dominated Rwandan Patriotic Front had put in place a temporary ceasefire between the factions. An opaque and very often meaningless racialist understanding of the Hutu majority and Tutsi minority had crystallized under German and later Belgian colonial rule between 1897 to 1959, during which colonial administrators entrenched the Tutsi elite as a kind of intermediary privileged class between the Europeans and the Hutu subaltern. Conceived by Europeans as a Hamitic peoples - still African, yet culturally superior to sub-Saharan “Negro” races such as the Hutu, Tutsis ruled Rwanda until a period of ethnic violence in 1959-1963, which saw both the removal of Belgian colonial authority and the Tutsi government, and presaged in miniature the violence to come.

Government-issued identity cards, which listed their owners’ ethnicities, enabled the targeted killing of Tutsi individuals; Hutu civilians were encouraged based on propagandistic rhetoric of past grievances and threatened ethnic livelihood to turn against their neighbors - state-sponsored radio broadcasts, for example, which characterized the Tutsi population as an existential threat to a democratic Hutu republic. The West’s responses were heavily criticized during and to an even greater extent in the horrific aftermath of the hundred days of genocide: in particular the role of the French in lending its “unconditional” support to the regime right until the onset of violence; of the United States in its inaction; of the United Nations peacekeeping presence already in Rwanda at the time, and its swift abandonment of Rwandans under siege. The genocide ended in July, when the Rwandan Patriotic Front defeated state military forces. The impact of this relatively short period of violence, which decimated the country’s infrastructure and whole parts of its population, continues to resound in present-day Rwanda both in the material destruction it wrought and in its incalculable, indescribable trauma.

The International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda (ICTR) twenty years on

Robert Bechtle (May 14, 1932 - )

Alameda Nova (1978)

6 Cars on 20th Street (2007)

Crossing Arkansas (1992)

Frisco Nova (1979)

’61 Pontiac (1968–69)

'63 Bel Air (1973)

Portrero Garage Arkansas Street (1995)

Robert Bechtle (May 14, 1932 - )

May 15, 1911: The revolutionary forces of Francisco Madero...

May 15, 1911: The revolutionary forces of Francisco Madero massacre over 300 Chinese residents of Torreón, Mexico.

In late 1910, with defeated Mexican presidential candidate Francisco Madero at its head, a diverse coalition launched what would unravel into the decade-long Mexican Revolution. Its fundamental consensus was that the regime of President Porfirio Díaz, which represented the dregs of colonial legacy, elitist Europeanism, and foreign collusion over the interests of Mexico, must be deposed.

Underlying these basic grievances was the even more fundamental, yet infinitely more complex, question of what the new Mexican nation should be. The thirty-four year-long Porfiriato dictated its national and social aims based on a strict positivist vision of progress, privileging all that was European and modernization in the image of the European. The questions facing those who now sought to overthrow Díaz were therefore charged with issues of race, xenophobia, and lo mexicano and mexicanidad. As the new revolutionary Mexico emerged - a nationalist Mexico, which now embraced the ordinary middle and lower classes and Mexico’s indigenous populations over the European-aligned upper classes - fissures elsewhere fractured violently open.

Some 10,000 to 40,000 Chinese resided in Mexico by 1910. President Díaz had hitherto welcomed enthusiastically both foreign capital and the foreign cheap labor provided by this stream of Chinese migrants. As was the pattern across the Americas, the Chinese lived and labored in mostly isolated cultural enclaves. At the same time, many Chinese workers managed to accumulate some capital and open businesses both large and small. By the time of the Mexican Revolution, a strong anti-foreign sentiment - directed at not only Americans but Asians who, like the Americans, appeared to be profiting and thriving at the expense of ordinary Mexicans - was clearly brewing.

Between May 13 to May 15, as Díaz’s exit became imminent, maderista troops took the northern city of Torreón, and in the process massacred an estimated 303 Chinese in addition to 5 Japanese residents who became conflated with the Chinese population. Lebbeus R. Wilfley described in his investigations of the massacre that “soldiers shot them as they would rabbits for sport and for practice in marksmanship,“ and then after the "carnival of slaughter ended [the soldiers] … robbed the dead.” A mob of over 4,000 civilians accompanied the soldiers and, incited by calls to “exterminate” this alien population of exploiters and profiteers, attacked Chinese businesses and slaughtered indiscriminately, despite some individual efforts by civilians to protect them.

The massacre ended by order of Emilio Madero, who then placed survivors under military protection, but the sentiment remained. While the scale of violence that took place at Torreón was never repeated, attacks against Chinese property and individuals continued through the revolution. In the years following, calls for exclusion or expulsion escalated, and the Chinese government, itself confronting foreign encroachment across the Pacific, could do very little to protect its overseas nationals.

May 16, 1916: The Sykes-Picot Agreement is ratified.One hundred...

May 16, 1916: The Sykes-Picot Agreement is ratified.

One hundred years ago today, French and British diplomats signed secret negotiations that would profoundly shape the geopolitics of the Middle East following the defeat and partition of the Ottoman Empire. The Sykes-Picot Agreement was not the singular machination by Western powers to define the post-World War I distribution of power in the Middle East; however, it has singularly come to epitomize the consequences of both the failures of the colonial past and of the strife in the following decades of continuous instability and Western interventionism.

Over the course of approximately five months, two relatively minor British and French diplomats, Mark Sykes and François Georges-Picot, roughly outlined the future mandates of Palestine, Jordan, Syria, Lebanon, and Iraq. As pictured above, Sykes and Picot’s map determined that certain areas (shaded blue and pink) would become subject to complete British or French discretion, while others (regions “A” and “B”) would become regions under European spheres of influence.

At the time of the agreement, the war was still far from over, and it was later postwar conferences and settlements that actually set in stone the basic ambitions of partition and imperial optimism outlined in Sykes-Picot. The implications of the mid-war agreement materialized in, among others, the Treaties of Sèvres (1920) and Lausanne (1923), and overall via the postwar mandate system. A wide range of geopolitical concerns, evolving over the course of war, governed the negotiation of Sykes-Picot, for example: access to the Suez Canal and Persian Gulf; the threats posed by Germany and Russia; access to regional infrastructure and finance; access to oil, in particular fields in Mosul, Iraq; of course, competing French and British claims also pushed and pulled the lines of division.

The terms of Sykes-Picot - and contained within, the flagrant bad faith of the Western negotiators toward Arab aspirations and budding Arab nationalisms - were not known to the public until its terms leaked in full to Russian newspapers in late 1917. This was within weeks of the publication of the Balfour Declaration, which pledged British support for a Jewish national home in Palestine.

The actual direct impact and relevance of the agreement one hundred years on continues to animate debate, but Sykes-Picot nevertheless occupies a special place in the decades-long tableau of turmoil in the Middle East as both the subject of scholarly analysis and as a powerful rhetorical tool, a shorthand for grievances rooted in colonialism. A vivid representation in the popular imagination prevails: of European colonizers drawing up arbitrary “lines in the sand,” divvying up Ottoman lands with no input from their inhabitants, conspiring against Arab leaders, and constructing an untenable system of Arab states whose nonsensical artificiality has magnified the frequency and depth of regional conflict - inadvertently, arrogantly, myopically, shaping the course of history in the Middle East. One famous contemporary - namely T.E. Lawrence - declared the agreement “geographically and politically absurd.”

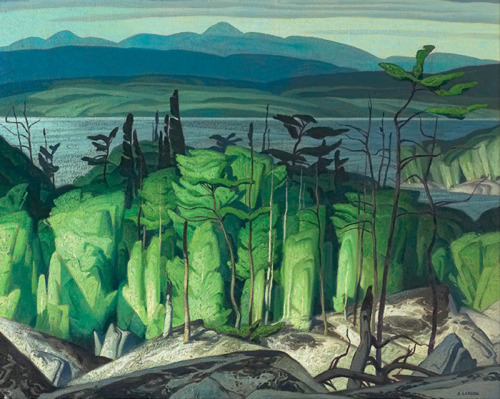

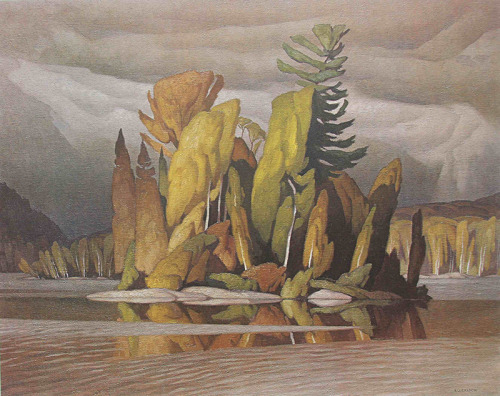

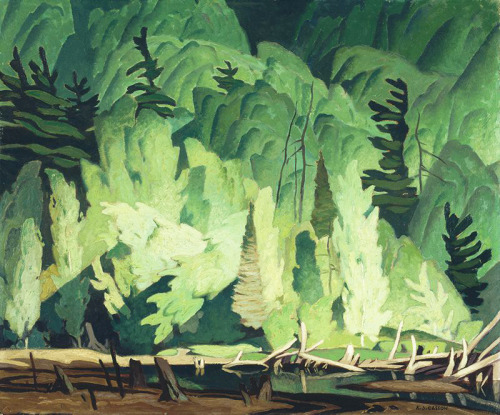

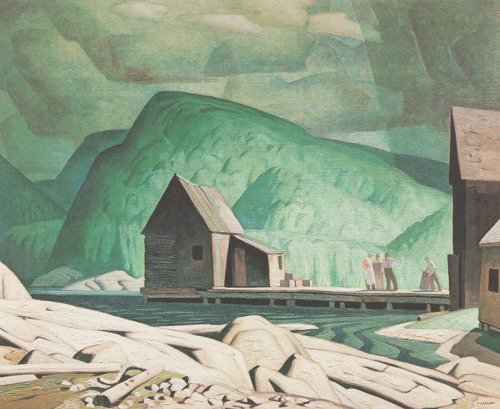

A.J. Casson (May 17, 1898 – February 20, 1992)

Bon Echo

Jack Pine and Poplar (1948)

Little Island (1965)

October (1928)

Summer Hillside (1945)

White Pine (1957)

Sun After Rain

A.J. Casson (May 17, 1898 – February 20, 1992)

Kapustin Yar (known today as Znamensk) is one of the Soviet...

Kapustin Yar (known today as Znamensk) is one of the Soviet Union’s first rocket launch and missile development sites. The test ground was established on May 13, 1946, and to mark its 70th anniversary Russia’s Defense Ministry has declassified revealing photographs of the site that offer a peek inside the top secret military complex.

Recently Declassified Photos Show the Birth of the Soviet Space Program

May 20, 1996: The United States Supreme Court hands down its...

May 20, 1996: The United States Supreme Court hands down its decision in landmark LGBT case Romer v. Evans.

Prior to Romer v. Evans, the United States Supreme Court had deliberated a limited number of cases related to LGBT rights, coming down both in favor of and in opposition to their advancement. In 1958, the Court ruled in One, Inc. v. Olesen to affirm right to free speech of a gay interest magazine against censorship by blasphemy laws. Nearly thirty years later, the Court upheld in Bowers v. Hardwick the constitutionality of a Georgia law and therefore any local and state statutes criminalizing homosexual sex as illegal sodomy.

The Supreme Court once again took up the issue when Richard G. Evans and three other individuals brought a suit against Colorado governor Roy Romer in opposition to Amendment 2 to the Colorado constitution. As gay rights activists made impressive strides across the nation, so then did a increasingly politically vocal, nationally mobilized Christian Right push back in equal measure. The “culture clash” that unfolded, centering on these tensions, embroiled the nation in numerous legal and political battles throughout the 1980s and 1990s. In 1992, Colorado voters passed an amendment to the state constitution that rescinded protections for individuals from discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation while precluding future protections of the kind. Evans’ challenge of the amendment passed to the Supreme Court in late 1995.

On May 20, 1996, the Court found in a 6-3 decision that Amendment 2, by transgressing the “commitment to the law’s neutrality where the rights of persons are at stake,” was in violation of the Equal Protection Clause. Justice Anthony Kennedy, writing for the majority opinion, described the Amendment as a “status-based classification of persons undertaken for its own sake,” whose flimsy justifications only “[raised] the inevitable inference that it is born of animosity toward the class that it affects” - homophobic pushback thinly and unconvincingly disguised as policy.

On the opposing side, Justice Antonin Scalia wrote in the dissenting opinion that the Amendment was merely a “modest attempt by seemingly tolerant Coloradans to preserve traditional sexual mores.” Scalia moreover accused the Court of siding “with the Templars” in a “culture war” in which the courts had no place. Of course, the Supreme Court’s engagement in the “culture war” only deepened following Romer v. Evans. In 2003, the Court’s ruling in Lawrence v. Texas overturned Bowers v. Hardwick and in effect all anti-sodomy laws still in place across the country.

La Noire de… (1966), Ousmane SembèneOusmane Sembène’s La Noire...

La Noire de… (1966), Ousmane Sembène

Ousmane Sembène’s La Noire de… (English title: Black Girl) (1966) turns fifty this year. Perhaps Sembène’s best known-film - and one of the first and to this day few African films to attract international attention, La Noire de… is a simple and straightforward narrative, stylistically understated, dreamlike, quietly melancholy. Beneath this subdued face churns fierce political anxieties and an emotional trauma cuttingly personal and individual, yet also broad and historical.

The travails and ultimate tragedy of one woman as she navigates post-independence Dakar and the French Riviera become intertwined with those of a nascent Senegalese state and those of entire peoples, the newly-independent populations of French West Africa, suspended in the uncertain condition of the “postcolonial.” (Mbissine Thérèse Diop, the film’s titular Girl, disputes allegorical interpretations.)

Sembène was, as an artist, first a novelist. He eventually embraced film for its accessibility and universal reach, a “medium that could reconcile the African artist with the millions of peasants, workers, and women, whom Aimé Césaire called “les bouches qui n'ont pas bouches” (those mouths without a mouth).” The heroine of La Noire de… is herself such a mouth, female, disenfranchised, illiterate - Sembène’s political and artistic concerns were often one and the same. La Noire de… shares with much of Sembène’s body of work, literary and cinematic, these political-artistic themes: explorations of African dignity in the face of the European; the struggle of women (many of Sembène’s films featured women; he once stated that“when women progress, society progresses”); the stagnation and rapid transformation and immeasurable contradiction of postcolonial society and identity.

Sembène, as committed to Marxism as he was to shaping an “indigenous” African cinematic form, described the style toward which he strove over his four-decade-long film career as “militant cinema.”

Hubert Robert (May 22, 1733 – April 15, 1808)

Girls Dancing Around An Obelisk (1798)

View of the Port of Rippeta in Rome (1766)

Temple of Philosophy at Ermenonville (1798)

The Arc de Triomphe and the Theatre of Orange (1787)

El Coliseo de Roma (1780-90)

The Bathing Pool

Hubert Robert (May 22, 1733 – April 15, 1808)

The Shining, Stanley Kubrick (May 23, 1980)Physically, it’s not...

The Shining, Stanley Kubrick (May 23, 1980)

Physically, it’s not a very demanding job. The only thing that can get a bit trying up here during the winter is, uh, a tremendous sense of isolation.

Well, that just happens to be exactly what I’m looking for. I’m outlining a new writing project and five months of peace is just what I want.

That’s very good Jack, because, uh, for some people, solitude and isolation can, of itself become a problem.

unhistorical: Happy October 11th, National Coming Out...

Happy October 11th, National Coming Out Day!

National Coming Out Day (1988), official logo, Keith Haring

Happy Pride month!

blkproverbs: “Me, We.” Muhammad Ali Rest in power king.

Muhammad Ali on refusing the draft in 1967

In 1967, Muhammad Ali was convicted of draft evasion for...

In 1967, Muhammad Ali was convicted of draft evasion for refusing to be inducted into the U.S. Army. His anti-war convictions stemming from his Muslim faith, and his status as a minister, he argued, exempted him from the draft; the courts disagreed. Ali was thereafter banned from boxing in the United States and stripped of his world heavyweight title by the World Boxing Association. Here, Ali is confronted by students who berate him for refusing the draft, and he responds.

Yet despite public outrage and criticism, Ali’s objections found famous support. As Dr. Martin Luther King began to voice public opposition to the war in early 1967, he - in spite of his strained relationship with the Nation of Islam - explicitly echoed Ali: “Like Muhammad Ali puts it, we are all—black and brown and poor—victims of the same system of oppression.”

Famed sportscaster Howard Cosell argued that “They took away his livelihood because he failed the test of political and social conformity… Nobody says a damn word about the professional football players who dodged the draft, but Muhammad was different. He was black, and he was boastful.”

One of the principal demands of the Olympic Project for Human Rights (OPHR), an organization that included Tommie Smith and John Carlos - whose Black Power salutes at the 1968 Olympic Games similarly shattered the illusory separation of politics, race, and sport - was the restoration of Ali’s heavyweight title. Harry Edwards, a key architect of the OPHR, proclaimed Ali“the warrior saint in the revolt of the black athlete in America.”

In 1971, the Supreme Court overturned Ali’s conviction and his denial by the lower courts of conscientious objector status.

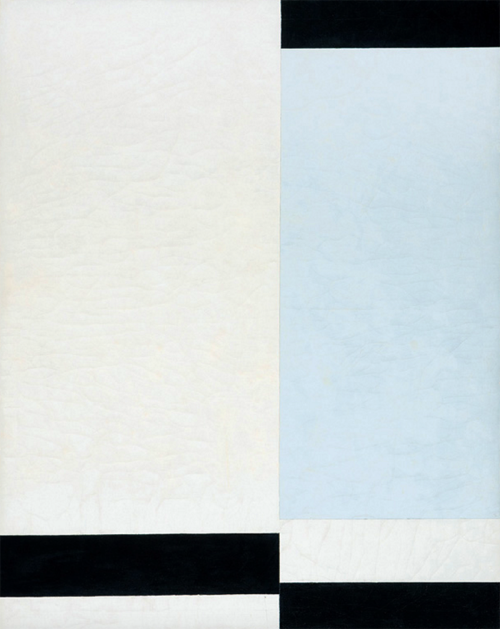

Untitled (1951) / Untitled (1958), John McLaughlin

Untitled (1951) / Untitled (1958), John McLaughlin

queergraffiti: “gay is good” “gay is great / right on...

“gay is good”

“gay is great / right on baby”

Washington Square Park, NYC (1970)

see more historical graffiti